When the TalTech chemistry and biotechnology institute doctoral student Aleksandra Murre (24) starts talking about chemistry, the words that fly out of her mouth are probably foreign to most Estonian language speakers, even those who speak it as a native language. “Atom economy” is followed by “achiral molecules”, and “catalytic reaction” embraces “dihydropyridine synthesis” with absolute nonchalance. It seems incredible that when she started her bachelor’s studies at the beginning of this decade, Aleksandra had a “very hard” time learning in Estonian. “It would be easier if your entire schooling would be in one language from beginning to end,” she finds.

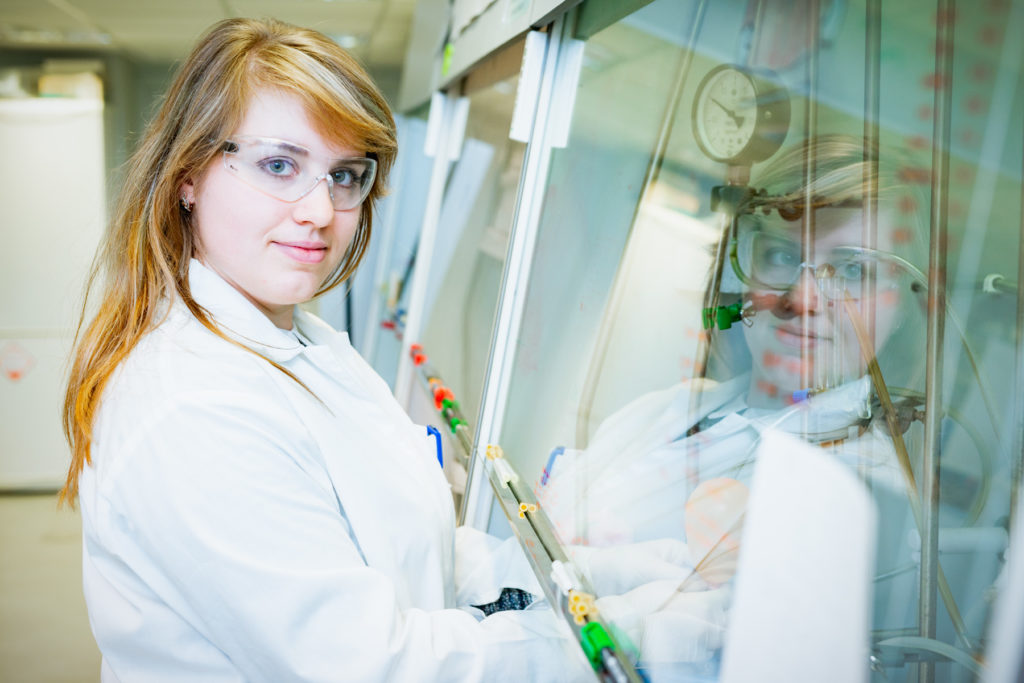

Like the term ‘applied chemistry’ implies, this is not an abstract subject, you need to use your hands. However, quite a few of the chemicals that the young scientist has already conducted experiments with are very hazardous, as she admits. There are some, which “in catalytic quantities could kill and you might not even realize that you’ve inhaled them,” which means that in the interest of safety she always has to work under a ventilator hood. Some substances are also explosives, and when conducting experiments with those, there is always someone else standing by with a fire blanket. “Usually, the rule is that you can’t work in a lab alone,” Aleksandra says in a serious tone. “You always have to have another person next to you, who knows what you are doing.”

At the same time, the work isn’t nerve wracking, at least not for Aleksandra. “I only get stressed if I’m working on an experiment for six months already, and it’s still not coming out. That’s when it starts to get on my nerves – why aren’t the molecules behaving in a way that I would like them to?”

One of the biggest setbacks so far was the time when Aleksandra was trying to develop an innovative method for synthesizing amino acids, however, the molecules were equipped with the “Evans chiral auxilliary”. “We had to get rid of it and I ran experiments for six months, but then I ended up circumventing the problem instead.”

Maybe one day you’ll shake that “Evans chiral auxilliary”, I try to console her, not even daring to imagine what this chiral auxilliary might be.

“I already gave up on that project,” Aleksandra replies quite concretely.

Her day of work at TalTech starts at eight thirty. “As a rule, I already have an experiment running from the day before, so I check on that first, then I isolate the product of the reaction, and then I identify it using analytical methods. If the reaction has ended, I register the result and clean the surfaces. Sometimes I get a great idea in the middle of the night and then I run to work in the morning, to get a new reaction started,” describes Aleksandra. However, her days are also filled to a large extent by reading (to see “how other people have solved a problem before”) and writing articles about experiments that have already been completed. “In parallel with that, I also have my courses and I have to write essays.”

“Do you always get everything done on time?”

“For sure! Before the deadline!”

“You’ve never missed a deadline?”

“I don’t remember ever being late, not once.”

Maybe Aleksandra’s sense of responsibility was cultivated by the hamster that she had as a child. The little animal lived to be 3,5 years old (“What a champ!” says Aleksandra), which is twice their normal life expectancy. Aleksandra has a theory about that – maybe it was because she ground up the seeds that she fed the animal every day. She also bought the little critter fresh sour cream every day. When it comes to prolonging human life and curing diseases, the solutions aren’t as simple as that, however, that is what Aleksandra is indirectly working towards. “Bringing chirality to an achiral molecul” in her words has a lot of perspective for the medical industry, especially the aspect, where “out of the many possible stereoisomers of a drug only one is active.”

I’m not even going to pretend that I understood that.

Something simpler: Aleksandra also likes to design tableware, for herself as well as for gifts. To make money, she has also worked as a sales clerk at the toy shop Karupoeg Puhh. She likes “drawing patterns” and go for long rollerskate rides around Tallinn. She does not want to talk about Estonian politics though (“I’d have to get another doctoral degree to understand that”). She has been to Russia only twice in her life. “Once as a child with my parents and then I was sick the entire trip, so I don’t remember much about that. The second time I went with a choir. I remember being stuck in traffic for five hours. I fell asleep, woke up, and we were still in the same spot.”

While so many young people are going elsewhere to Europe and beyond for their degree studies, has Aleksandra not felt the temptation to go abroad?

“Actually, I did think about it, I think I even applied somewhere, but then I changed my mind and decided to stay here,” Aleksandra candidly says. “First of all, my current topic of research is very near and dear to my heart, and second, someone has to do research in Estonia too. If everyone leaves, there will be nobody left here.”

FIVE QUESTIONS

CITY OR COUNTRY: “City! I like having a lot of options close by.”

CAT OR DOG: “Both.”

WHITE OR RED: “Red.”

TEA OR COFFEE: “Coffee.”

LEFT OR RIGHT: “Jesus! Right.”